Newsletter

All around the globe, people suffer from the ill effects of air pollution. An insidious killer that targets the young and old alike, air pollution is responsible for around seven million premature deaths each year and propagates a range of severe health concerns.

While most people are generally aware of the detriments of air pollution, we tend to think of it as something limited to smoggy cities like New Delhi or Beijing. Air pollution has become a topic of faraway places, far removed from where we live. However, air pollution is often much closer to home than we realize.

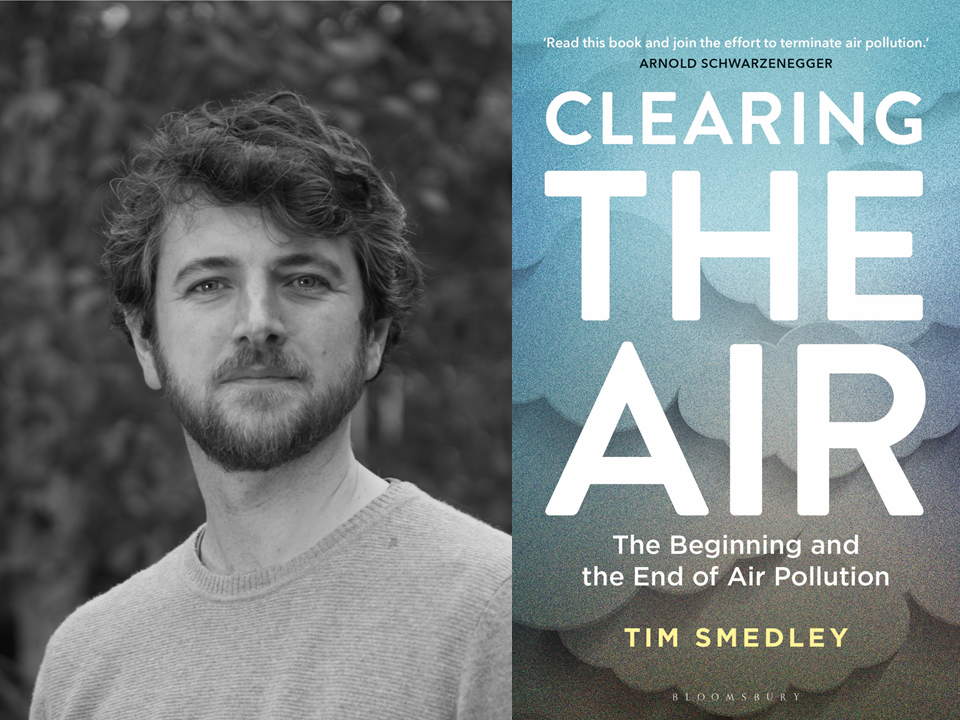

Kaiterra’s mission has always been to bring awareness to air pollution and one day rid the world of air pollution, so we invited Tim Smedley, author of Clearing the Air: The Beginning and the End of Air Pollution, to join us today to discuss this issue. Smedley’s book documents his journey as a new parent navigating the complicated field of air pollution research and the nuances of social, health, and environmental repercussions of air pollution.

No stranger to environmental issues, Smedley began his journey as a sustainability journalist writing for the Guardian and the Financial Times. While generally aware of the dangers of air pollution, he always thought of air pollution as a far-away and removed issue. When he saw an article published in the Evening Standard, “Oxford Street has worst diesel pollution on Earth,” he was taken aback. He recalls, “I was completely blindsided...there was an environmental crisis happening literally happening on my doorstep and I didn’t know about it.”

In the midst of his shock, Smedley began to view this issue through the lens of a father. Smedley remarks, “I became a parent at the same time as learning about air pollution, so this suddenly made it all the more real, and personal, to me.” This connection drove Smedley to start looking into air pollution, the damage it has caused, the lives it has taken, and dive into air pollution research.

“I became a parent at the same time as learning about air pollution, so this suddenly made it all the more real, and personal, to me.”

- Tim Smedley

One of Smedley’s major challenges dealt with often-siloed scientific research. Because air pollution is such a broad issue, many different scientific fields are involved in air pollution research, including atmospheric chemistry, combustion engineering, and meteorology. There is a similar problem with research on the health effects of air pollution. To understand the overall physiological impact of air pollution, Smedley had to dive into cardiology, epidemiology, and more.

Smedley valued the challenge. “In the end, being an outsider became a real advantage – often people work in very narrow fields and silos and don’t get the chance to speak with people from related fields. By talking to all of them, I could begin to put the pieces of the jigsaw together.”

Throughout his travels incorporating London, Beijing, Paris, and New Delhi, Smedley used the Laser Egg to measure pollution in different city areas. "We don’t spend our lives standing still, we spend them on the move. We can live in a polluted city and learn to reduce our exposure, and similarly, we can live in a ‘clean’ city, and still be exposed to very high levels of pollution. My Laser Egg gave me a snapshot reading wherever I was on my travels, inside trains, on the backseat of taxis, even lodging in rooms as smoke drifted in through the window." Smedley found his cleanest readings in Helsinki, Finland, where even along busy streets, PM2.5 readings were only single digits. His highest readings, by far, were in Delhi, where PM2.5 readings were in the 300s for much of his time there.

Seeking a blueprint for eliminating pollution, Smedley also discovered that while individual cities face their own complex pollution conditions, air pollution remains very much a global issue, with commonalities tying cities together. In particular, Smedley identifies a “pollution lifecycle.”

“Every major city has a very similar pollution lifecycle. It begins with an industrial boom within the heart of the city, fed by coal and other fossil fuels, followed by a rapid increase in road infrastructure to deliver people, goods and raw materials into that city.”

- Tim Smedley

For example, London used coal and wood to power the city, which caused the Great Smog of 1952, an event that killed 12,000 people. Afterward, the UK’s Clean Air Act (1956) was passed, but the rise of the automobile brought back NO2 and PM2.5 pollution, and a 21st Century resurgence in the popularity of wood stoves feeds black smoke within the city once more. Beijing, New Delhi, Paris, and Los Angeles followed similar paths, with varying degrees of success in fixing pollution.

Cities like Beijing, New Delhi, and London followed similar air pollution lifecycles

What struck Smedley as frustrating was the fact that air pollution is a solvable issue that’s slow to change and masked by denial. “It’s the children’s lungs studies that I come back to again and again, when people say ‘oh air pollution is made up, it doesn’t do me any harm.’ Well it did, it does, and if you have a family with children, it is doing them harm right now.”

Defeatism around air pollution was another of the myths surrounding air pollution that Smedley hopes to debunk with his book. The scale and severity of air pollution may make people think that we don’t have the power to help stop air pollution and that there isn’t anything we can do. Yet, with air pollution, this is not the case.

While the pace may be frustrating, change is possible. The technology is available. “Because urban air pollution is local, short-lived, and can be stopped at the source; the benefits of doing so are instant and dramatic.” The first step is reducing our appetite for fossil fuels and removing combustion from the equation. Moving to renewables, expanding and electrifying public transportation, and installing pollution-absorbing ‘green walls’ such as hedges and ivy can all cut down air pollution.

Because air pollution is a global issue, everyone has a role to play in stopping air pollution. Around the world, individuals and companies alike, have the potential to reduce air pollution in their own way. Companies can switch to electric delivery trucks and promote air pollution awareness, and people can reduce their footprint by switching to electric themselves, taking public transportation, using pedal power, and simply spreading awareness by informing friends and family about air pollution.

As Smedley said, by joining together, we have the power to make changes and stand up for a healthier future.

“Whether this zero-emissions, low-carbon future happens in 10, 20, or 100 years, is down to public pressure and political will. It’s down to us.”

- Tim Smedley

Editor’s Notes:

Big thanks to Tim for sharing his insights with us. In fact, there’s so much more we covered in the interview, but because of the length of this post, we can’t include everything here. Feel free to download the full interview transcript here and dig deeper into this conversation:

To read more about air pollution, check out Tim Smedley’s book Clearing the Air here.

.png?width=200&height=148&name=Menu%20C%20(2).png)

.png?width=307&height=228&name=Menu%20-%20D%20(1).png)

.png)